The most enjoyable aspect of my PhD research so far has been the discovery of myriad different perspectives on the history of technology, written by a range of media ecologists.

Occasionally, in such reading, I have discovered a study or views that challenge my preconceived ideas or in one particular recent case, have even challenged my identity. I experienced exactly this while reading a 2002 article titled The Development of Graphical User Interfaces and their Influence on the Future of Human-Computer Interaction, written by Susan Barnes.

In this journal article, Barnes (2002) explains that the realisation of the graphical user interface (GUI)—upon which all desktop computers (and subsequent mobile devices) are based—was the result of four distinct stages of development: (1) the ‘ideals-driven’ stage; (2) the ‘play-driven’ stage; (3) the ‘product-driven’ stage; and (4) the ‘market-driven’ stage. To explain this further, Barnes (2002, p. 81) outlines the history more specifically:

In the first stage, Douglas Engelbart conceived certain ideas about how people should ideally interact with computers and he developed computer systems that incorporated those ideals. The resulting technology was next expanded and elaborated, in the play-driven stage of development, by Alan Kay and his fellow researchers at Xerox PARC. In the third stage, the PARC prototypes were later turned into commercial products by Apple Computer. Finally, in the market-driven stage, Apple, IBM, and Microsoft started competing with each other in the development of GUI technology in hopes of dominating the enormous technology marketplace.

It is the product-driven stage to which many Apple fans would cling, as the narrative tells us that Apple refined and popularised this concept for accessible (indirect) computer interaction with a mouse.

As an Apple fan from early childhood—growing up with a Mac—the philosophy and brand of the company has long been a part of my identity. I accept and respect the advantages of other PC brands and vendors but much prefer what Apple offers. This quote from Barne’s (2002, p. 88) article seems to justify this achievement:

The Macintosh was the bridge into the fourth stage of development, the market-driven stage. Bill Gates took Macintosh’s Desktop Finder interface and with minor modifications marketed it as Microsoft Windows.

That is, until I read further into the article and discovered the following section, which explains how the development of the graphical interface and its grander purpose at Xerox PARC was cut short (Barnes, 2002, p. 90):

…the results of this study suggest that, a pivotal moment in the history of graphical interfaces was Jobs’s decision to apply the visual screen elements to Apple computers without the underlying programming language. Jobs’s intention was primarily to sell computers, and in the interest of that objective he largely ignored the social and cognitive ideals underlying the earlier designs. Today, Jobs’s decision can be viewed as a historical turning point that created paradoxical situations for the future development of GUI development.

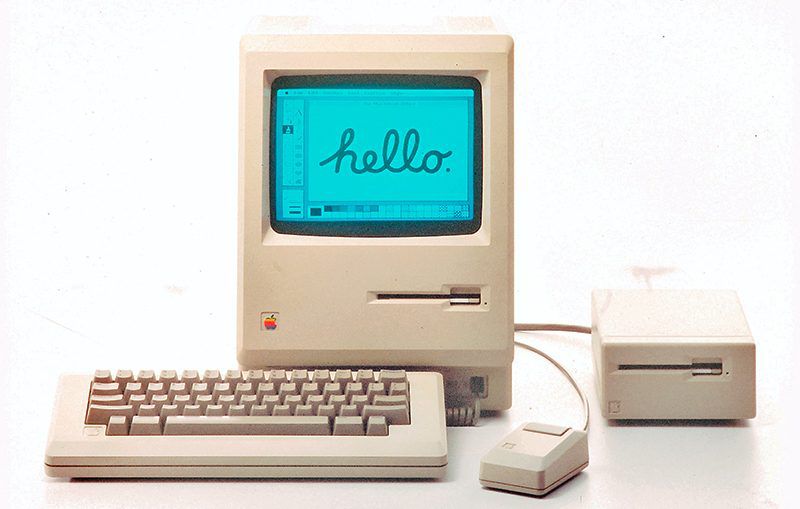

When the original Macintosh was released in 1984, it was hailed as the computer ‘for the rest of us’. It was supposed to be intuitive and more accessible to a wider range of people than early command-line-driven computers were. For those who remember, IBM was the enemy at the time. With Barnes’s (2002) study and assessment of Apple’s role, she challenges this history (or myth, if you prefer), by saying that Apple essentially cut the development of the GUI short.

I was already aware of the story of Jobs’s visit to Xerox PARC and adoption of the GUI idea, however I was unaware of this approach to the story. I had always viewed the release of (then) Mac OS as the ultimate popularisation of accessible computing, rather than the inhibitor to a wondrous future of true digital and technological literacy.

Instead, Barnes (2002) essentially argues that by releasing a personal computer in the form of an easy all-in-one appliance, Apple completely closed the platform to investigation and comprehension by users through education about how to program properly, thus creating what Innis would call a ‘monopoly of knowledge’ with a business and profit-driven intention. In his book Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology, media ecologist Neil Postman (1993, p. 3) defines Innis’s term: ‘…those who cultivate competence in the use of a new technology become an elite group that are granted undeserved authority and prestige by those who have no such competence‘.

Ultimately, by making it easy to use, Apple stopped people (other than programmers/developers) from ever really learning how a computer works. As an enthusiastic user who isn’t a programmer, I would fall into this category and of course, I pay handsomely for Apple stuff.

This is quite the challenge to my entire idea of Apple’s role in modern computing. I have long acknowledged the company’s tendency to prefer more closed, all-in-one systems and consumer electronics, however I never saw Apple’s legacy as one that is negative or deliberately limiting. As Barnes (2002) puts it, Jobs (as more of a sales guy) was apparently unable to comprehend anything beyond the visual, hence the focus on iconography and desire to dumb things down for the average user.

While I am happy to remain open to this more complex idea of Apple’s role in the history of the GUI (along with Microsoft’s, which is also blamed), I do believe that there is a somewhat utopian—if not slightly elitist—element to Barnes’s (2002) argument. In his book The Story of Utopias, Mumford (1962, p. 1) defines the word utopia as the precursor to a discussion of broader society’s idealism and ideas of what it means to live a good life:

The word utopia stands in common usage for the ultimate in human folly or human hope—vain dreams of perfection in a Never-Never Land or rational efforts to remake man’s environment and his institutions and even his erring nature, so as to enrich the possibilities of the common life. Sir Thomas More, the coiner of the word, was aware of both implications… he explained that utopia might refer either to the Greek “eutopia,” which means the good place, or to “outopia,” which means no place.

I can’t help but feel that although Apple and Microsoft might have doomed the broader masses to never attaining the full knowledge of computer programming, the idea that the entire global community would be educated to the point of expert computer programming seems very hopeful and utopian. As we can see today, even with ‘dumbed-down’ GUIs and product designs, many from older generations who grew up alongside or worked during the development of computers and the Internet still struggle to navigate apps and operating systems. The view of modern computing as unnecessarily stripped back and made to be less intelligent sounds like a mildly elitist view of the entire way that people enjoy using computers today. One can be somewhat hands-off. Indeed, the way that Apple and Microsoft ended up designing such products empowered people who were most likely never going to be interested in programming the first place.

I believe that the truth lies somewhere in the middle. Sure, Apple took the idea of the GUI and potentially limited its development as a more powerful, mainstream programmer’s tool, however it also gave people the chance to work and create art without the need to become a programmer.

It is easy to criticise people’s and companies’ roles throughout history and as a massive influence on the global community, corporations like Apple should never be immune to scrutiny. As I delve deeper into my research on podcasting, which is a result of my Apple fandom, I need to remain open to views that challenge my preconceptions of how technology works, how it has been developed and how it affects people in ways both big and small. My views on what constitutes things like computing, media consumption and podcasting in general may not align with others’.

References

- Barnes, S.B., 2002, ‘The Development of Graphical User Interfaces and their Influence on the Future of Human-Computer Interaction’, in Explorations in Media Ecology, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 81–95.

- Image credit: MacRumors (2019)

- Mumford, L., 1962, The Story of Utopias, Viking Press.

- Postman, N., 1993, Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology, Vintage Books, New York.